CS 2120: Class #15¶

Some things¶

Let’s draw a Koch Snowflake on the board.

Let’s write a program that does this:

Let the user pick some complex parameter c For every complex number (r,i) in a bounded plane: z = c while z is not *really big*: z = z*z + c if z has convereged, this point is 'in' this point is 'out'

(Mathematically, of course, really big isn’t enough, we’re looking for values that diverge to infinity... but Python doesn’t do infinity so well, so here we are)

A full Python version is here

Let’s plot that set (black dot for elements in the set, coloured dot otherwise – colour indicating how fast the value goes to infinity), and then zoom in on it: Mandlebrot zoom

Activity

What do all of these things (The Escher Drawing, the Bach Fugue, the fractals) have in common?

Activity

What does the following Python code do. Try to figure it out without running it. What’s new about how it works?:

def my_func(n):

if n < 1 :

return 0

else:

return n + my_func(n-1)

- We have discovered recursion.

- Hold onto your hats folks!

Let’s go back and trace the execution of our function on the board (pencil & paper debug) for a test case.

Activity

Fill out the instructor evaluations!

Warning

Pay really close attention here. The intuition we’re going to gain from walking through this simple example is critical.

Recursion¶

If a function calls itself, it is said to be a recursive function.

You’ve seen recursion before in your math classes (e.g., recurrence relations)

- Why would you want to have a function call itself??

- Well, maybe you want to repeat a section of code multiple times...

- ... like a loop!

Anywhere you can use a loop, you could also use recursion. The underlying effect is the same: repeating a chunk of code multiple times.

The semantics of how that happens are a bit different.

Some languages (e.g., Scheme) forbid loops and allow only recursion.

Some languages (e.g., Fortran 77) forbid recursion and allow only loops.

Most allow both because some problems are easier to solve with loops... and some are easier to solve with recursion.

There is nothing that can be done with recursion that can’t be done with loops (and vice-versa). This is a mathematically provable theorem.

However, some things are a lot easier with one or the other.

Thinking Recursively¶

To really “think recursively” requires us to rewire ourselves a bit.

Recursion is, without question, the most difficult CS1 topic for most students.

If you’re frustrated, stop me and ask questions.

Recursion is so incredibly powerful in some instances, that you simply can’t be a good programmer without mastering it. But that takes time. Expect frustration.

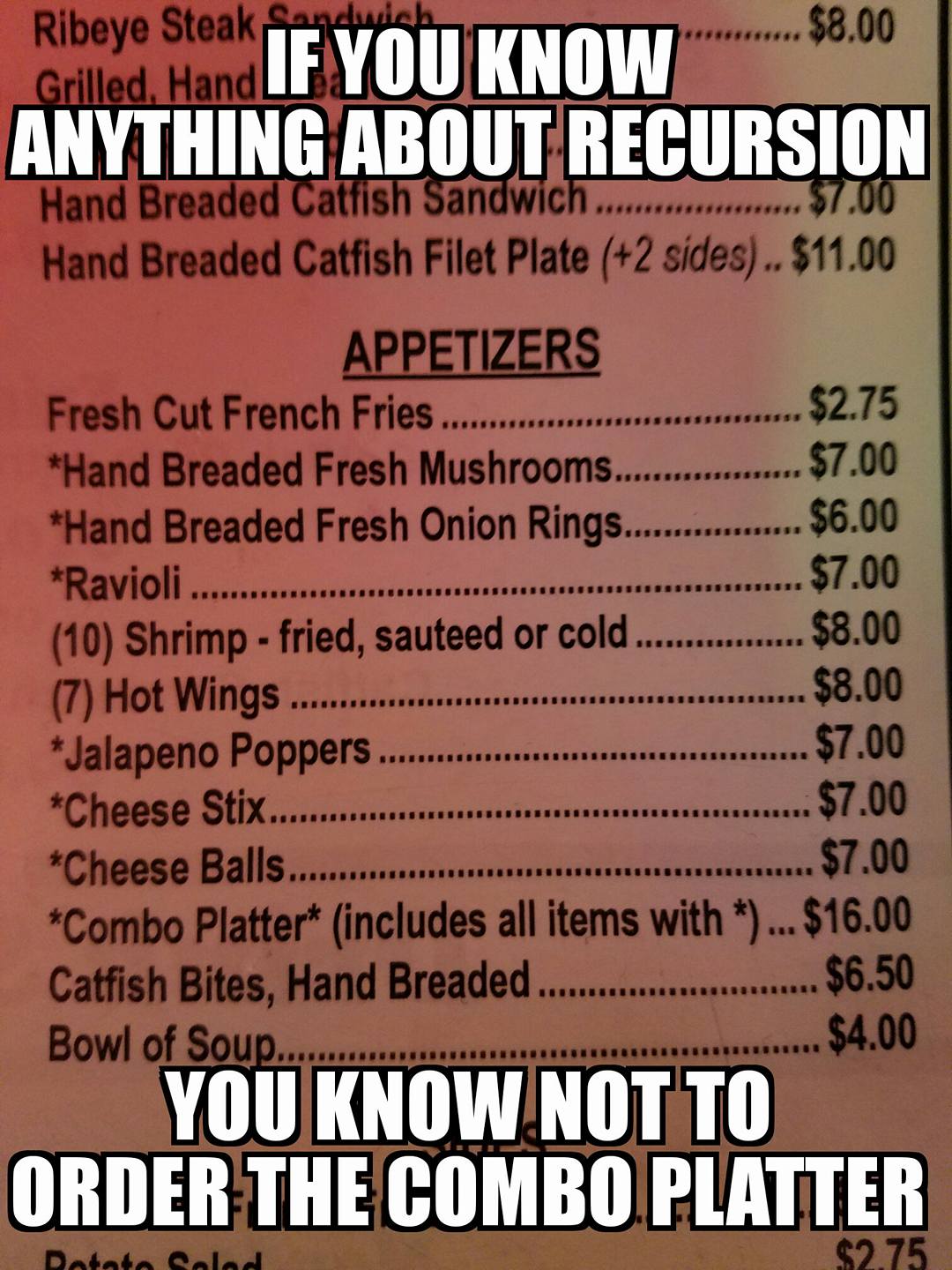

The dark side of recursion¶

Activity

I’ve modified the function we wrote above to add up only every other number.

Try running this new version with the call my_func(8).

Now try: my_func(7). What happened? Can you figure out how to fix it? (assuming you didn’t want this to happen):

def my_func(n):

if n == 0:

return 0

else:

return n + my_func(n-2)

Writing a simple recursive function¶

I’m going to give you some rules for writing recursive functions.

By following these rules, we can avoid the catastrophe we just had.

(When you get sophisticated enough, you’ll find situations in which it’s OK to stretch/violate these rules.)

- Every recursive function needs two things:

- A base case that terminates the recursion.

- A recursive step that calls the function again, but with a modified (probably smaller) parameter.

Activity

Identify the base case and recursive step in this function:

def my_func(n):

if n < 1 :

return 0

else:

return n + my_func(n-1)

Now it’s your turn:

Activity

Using “the rules”, write a function fact(n) which computes the factorial

of n using recursion (no loops allowed!!). Remember that factorial

is defined as n! = n * (n-1) * (n-2) * ... * 2 * 1. So, for example,

5! = 5 * 4 * 3 * 2 * 1 = 120 .

Recursive Data Structures¶

Recursive algorithms often work best with “recursive data structures”.

- Recursive data structures break down similarly to our approach to recursive algorithms:

- base case : a single piece of data (e.g., an integer)

- recursive case : everything else in the data structure

Activity

So far, we’ve been thinking of lists as collections of values. Try to come up with a recursive formulation for a list.

- Got it? Good.

Activity

Write a function sum_list(l) that will return the sum of adding up

all of the elements of l. You may not use loops! Assume that l

is a list of integers.

- We can think of lists as recursive, or non-recursive, data structures, depending on what we’re trying to do with them.

- This is true for any data structure, though some are much more naturally thought of in one way or the other.

Quicksort¶

You give me a list called

inlistIf the list has only one element, just return the list without doing anything

I pick an element from the list, which I’ll call the

pivot- I partition the list by shuffling the elements around so that:

- all elements less than

pivotare to the left ofpivot - all elements greater than

pivotare to the right of it

- all elements less than

- I recursively call quicksort on two lists:

- The list of stuff to the left of

pivot - The list of stuff to the right of

pivot

- The list of stuff to the left of

Activity

Do a quicksort, with pencil and paper, on the list [3,7,15,9,4,11,1,5,2].

Record the value of your list at each step.

You can see why we waited to study Quicksort.

- The idea of recursion is central to the description

- You can, of course, implement quicksort without using recursion, but it’s a bit uglier.

Thinking recursively, it’s a very clean divide-and-conquer strategy.

Let’s try it:

def partition(list, l, e, g): while list != []: head = list.pop(0) if head < e[0]: l = [head] + l elif head > e[0]: g = [head] + g else: e = [head] + e return (l, e, g) def quicksort(list): from random import choice print list if list == []: return [] else: pivot = list[0] less, equal, greater = partition(list[1:],[],[pivot],[]) return quicksort(less) + equal + quicksort(greater)

Activity

Modify the quicksort() function above so that it prints out the value of list every time it is called.

Try sorting a few lists and following the output.

Activity

What is the base case in quicksort() ?

What is the recursive case?

There are no loops... so how do I figure out how long it takes to sort a list with n elements? In the worst case? In the average case? Do you think this is a good sort? How does it compare to selection or insertion sort?

A definite improvement, but still not great in the worst case. Can we do better?

Mergesort¶

You give me a list,

inlistwithnelementsI divide

inlistintonsublists, each having 1 element.The sublists are now already sorted! (Any list with only one element is automatically sorted)

- I now begin merging sublists, to produce bigger (but still sorted) sublists:

- I compare the first element in one sublist to the first in the other

- Whichever is smaller goes into the merged list

- I now compare the second element in that list to the first element in the other list

- ... and so on...

I keep going until there is nothing left to merge (there’s only one big, sorted, list)

Activity

Do a mergesort, with pencil and paper, on the list [3,7,15,9,4,11,1,5,2].

Record the value of your list at each step.

Let’s start by implementing a

mergeoperation in Python:def merge(left, right): merged = [] l=0 r=0 while l < len(left) and r < len(right): if left[l] <= right[r]: merged.append(left[l]) l = l + 1 else: merged.append(right[r]) r = r + 1 if l < len(left): merged.extend(left[l:]) else: merged.extend(right[r:]) return merged

Activity

Try merging some lists with

merge.Remember:

mergeexpects that the lists it is merging are already sorted!! If the lists to merge weren’t already sorted, what would have to change aboutmerge?

Okay, now the real deal:

def mergesort(list): if len(list) <= 1: return list else: midpoint = int( len(list) / 2 ) left = mergesort(list[:midpoint]) right = mergesort(list[midpoint:]) return merge(left,right)

Wow, that was short! WTF is going on in there?

Activity

Modify the mergesort() function above so that it prints out the value of list every time it is called.

Try sorting a few lists and following the output.

Activity

What is the base case in mergesort() ? What is the recursive case? How many recursive calls will I make to mergesort() for a list of size n on average? In the worst case?

Recursion¶

This has been a tiny taste of recursion.

If you take more CS courses, you’ll see more recursive algorithms and you’ll develop an intuition for when it’s advantageous to use recursion.

- The official “learning goals” for this class though, are much more modest:

- Exposure to recursion

- Ability to define recursion

- Ability to recognize recursion in a Python function

If you actually understand recursion with no effort, then you are way ahead of the curve and should consider a CS major.

- If you don’t totally “get it”... you’re normal. Here’s the secret to “getting it”:

- Practice.

The even darker side of recursion¶

- Let’s start with a warmup:

Activity

Is the following statement true or false: “This statement is False.”?

Activity

What happens when Pinocchio says: “My nose is going to grow now.”?

- And then get down to business...

Activity++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Can you write a Python program that will look at a Python function and determine if the function might go into an infinite loop?

Let’s assume the answer to this activity is “yes” and see where that gets us.

Based on our assumption, I can write a function called

youre_screwed(func)that takes some arbitrary Python functionfunc()as its input.- If

func()goes into an infinite loop,youre_screwed()prints “Infinite loop infunc()” andreturns - If

func()doesn’t go into an infinite loop, this (perverse) function,youre_screwed(), does go into an infinite loop (I told you it was perverse).

- If

So... what happens if I execute:

>>> youre_screwed(youre_screwed)

???