CS 2120: Class #7¶

A note on comments¶

You can add comments to your code in Python with

#:do_something() # We just did something # Now we'll do something else do_something_else() # doing something else

As soon as Python sees

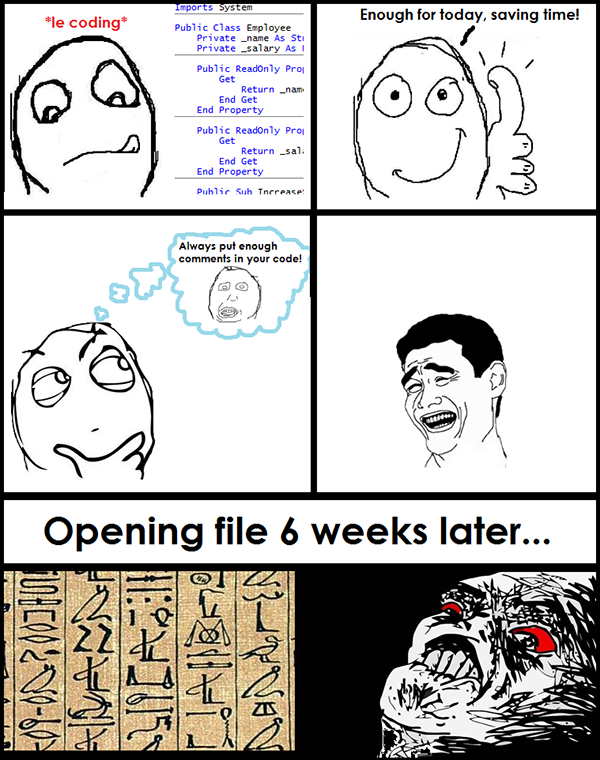

#it ignores the rest of the current lineWriting comments makes your code easier to read

Especially 6 weeks later when you have to change it

- And especially when someone else has to make sense of your mess

- Comments shouldn’t just repeat what’s obvious from reading the code

- They should provide a higher level description of what’s happening.

- Computer Scientists get real geeky about comments

- Physicists immediately go into shock and collapse if they write a single comment

- Find a healthy balance that works for you

Function headers¶

Because so much of our programming consists of pasting together functions... it is of special importance to document what a function does.

We do this with a function header:

def set_up_cities(names): """ Set up a collection of cities (world) for our simulator. Each city is a 3 element list, and our world will be a list of cities. :param names: A list with the names of the cities in the world. :return: a list of cities """ print 1+2

The stuff between the “”“s is the function header and should appear immediately after the

def.It should explain what the function is going to do, in plain English. If I have to read the function code to figure out what it does, your header description sucks.

It should explain every parameter.

If the function returns something, it should explain that too

This might all seem like a lot of extra work. And it is. But it’s less work than trying to figure out how everything works after you’ve been away from the code for 2 months.

You don’t believe me. You’ll leave this course and go write code with no comments. Seriously, you will. You might mean to write comments, but you won’t. You’re just too busy.

Then, at some later point, you’ll have to go back to your code. It won’t have comments. You’ll have no clue how anything works. It’ll take you a day or two just to figure out what you’d done before.

After that happens enough times, you’ll start writing comments.

The thing about strings¶

Activity

How is a string different from the other data types we’ve seen (int, float, numpy.float32, bool)?

I can print individual characters of a string, by indexing the string:

>>> a='My little string' >>> print a[0] M >>> print a[1] y

In a compound object, indexing allows us to pick out individual components.

- Note that in Python, the first index is

0, not1! - Whether to start at zero or one is an arbitrary decision made by programming language designers.

- Is the “first floor” of a building the same as le “premier étage”? Natural language problem, too!

- Python inherited the 0-based convention from C (this actually makes sense if/when you learn about memory pointers)

- MATLAB inherited 1-based indexing from Fortran

- This is a small gotcha for folks switching from one language to another; very easy to fix, but perplexing if you don’t know to look for it!

- Note that in Python, the first index is

Activity

Write a single line command to print the first 4 characters of some string a.

How about the 2nd to 7th characters?

How about the last three characters?

Hint: what does a negative index do?

Bonus if you’re reading ahead: what does

print a[0:4]do?This is called slicing the string.

More loops¶

- I can get the length of string like this:

>>> len(a) 15

Let’s apply that...

Activity

Write a function vert_print that takes a string as an argument and then uses a while loop to print each character on its own

line. (See sample output below)

>>> vert_print(a)

M

y

_

l

i

t

t

l

e

_

s

t

r

i

n

g

The

whileloop certainly worked OK there, but it was a bit awkward.whileloops are meant to continue until some logical condition is met.- Which this technically is, buttttt...

Maybe there is another kind of loop that says “Do the indented code block once for each item in a compound object” rather than “Do the code block until an arbitrary condition is met”.

Such a thing exists: the

forloop:for char in a: print char

for each character in the string

a, we run the indented code block.You don’t have to use the

forloop. Awhileloop can do exactly the same thing.The

forloop is just cleaner here (and less typing!).But there is nothing wrong with the

while! There are just a lot of ways to solve a problem.- You can actually prove that there are a (countably) infinite number of programs to do any given task.

- Some are just more efficient, and easier to read, than others.

Mutability¶

So... if we can access an individual character in a string with an index...

... you might be feeling tempted to try to set an individual character with an index, too.

- Let’s try::

>>> a[7]='X' Traceback (most recent call last): File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module> TypeError: 'str' object does not support item assignment

Variables of some types (like

int) are mutable... that is: they can be changed.Based on the above... do you think strings are mutable?

- You can’t change a string. You have to make a new one

>>> new_a = a[:7] + 'X' + a[8:] >>> print new_a My littXe string

in¶

Activity

Write a function char_is_in(char,string) that returns True if the character char appears

in the string string.

- HINT: what does the

inoperator do in Python? - You can do the above exercise the hard way, with loops, or you can look up

in.

Activity

What’s wrong with this?:

def char_is_in(char, string):

count = 0

while count < len(string):

if string[count] == char:

return True

else:

return False

count = count + 1

- Try: char_is_in(‘t’, ‘test’)

- Try: char_is_in(‘z’, ‘test’)

- Try: char_is_in(‘e’, ‘test’)

Activity

Write a function where_is(char,string) that returns the index of the first occurence of char in string.

Heavy lifting with strings¶

- If the program you are writing needs to do a lot of string manipulation, you probably want to

>>> import string

... and read about all the nifty stuff it does .